A Quick Sonnet Lesson

by Jessa R. Sexton

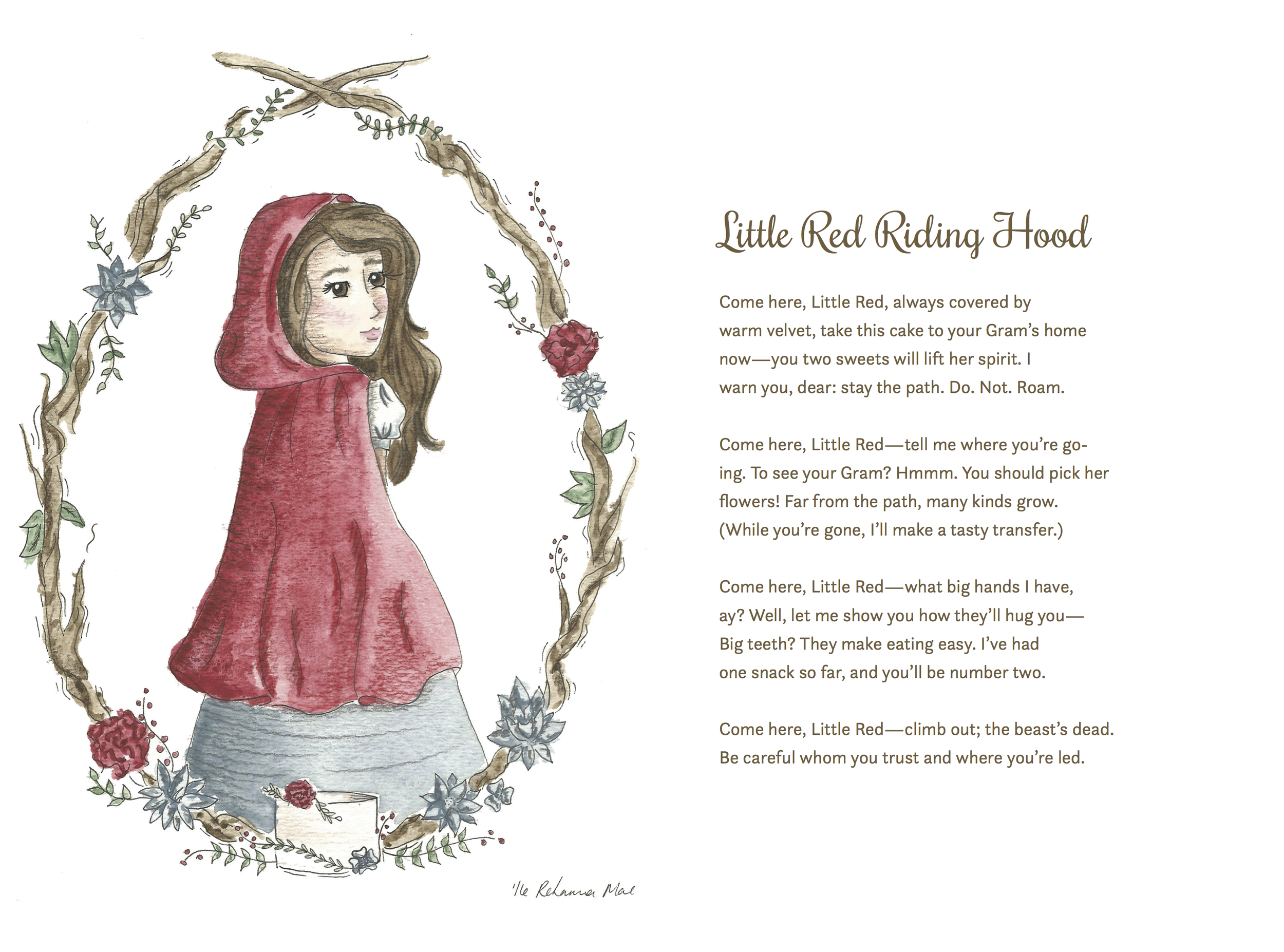

This year I released Stories of Enchantment and Little Stories of Enchantment. Each of these books is filled with twelve fairy tales I’ve condensed into sonnet form—these have been gorgeously adorned with portraits of the main characters by illustrator Rehanna Mae Grant. There are two versions. The red copy contains the sonnets, illustrations, and the classic fairy tale itself as well. The green copy is for littles: it’s more of a picture book style with just the twelve sonnets and illustrations.

So one of the first things you might think when you’re looking at the book cover is What is a sonnet? Don’t feel too bad for wondering that. I’ve been asked this question before. And what I want to do in this blog is give you the quickest poetry sonnet lesson, using “Little Red Riding Hood,” below, as an example.

Sonnets are a poem form, like a haiku or limerick. There are really THREE MAIN elements that you need to know when writing a sonnet:

1) number of lines,

2) line lengths or meter, and

3) rhyme scheme.

So—#1. A sonnet has 14 lines. That’s right—I looked over an ENTIRE fairy tale and tried to summarize it or capture the main themes and feelings in just 14 lines.

#2 is the line length or meter. Each of those 14 lines is ten syllables.

If you want to know the technical term, it’s called iambic pentameter. Just like a pentagon has 5 sides, this is called iambic pentameter, because there are 5 iambs. And an iamb is the combo of two syllables sounding like du DUH (one unstressed and one stressed).

It’s crazy how much math sonneteers have to do, huh?

If you didn’t catch the multiplication there:

an iamb is two syllables x five iambs per line = 10 syllables per line.

If it seems complicated, just remember that: 10 syllables per line.

And a sonnet, if read with the meter exaggerated, sounds like this:

Come here, Little Red, always covered by

warm velvet, take this cake to your Gram’s home

now—you two sweets will lift her spirit. I

warn you, dear one: stay the path. Do. Not. Roam.

Kind of like a galloping horse. But the beauty of this poem form is that the meter is there, but you don’t read like an equestrian—you read to the punctuation.

Say that with me, because it’s really the most important poem lesson I could ever give you ever: READ TO THE PUNCTUATION. That’s how the poem should ebb and flow—not like a jolting horse ride, but like a lyrical story.

Watch my film debut in the video below to hear how the "Little Red Riding Hood" sonnet should be read.

READ TO THE PUNCTUATION. Got it? Good.

Okay, we’ve talked about the sonnet having 14 lines.

And we’ve talked about each line having 10 syllables.

So the final thing I need to point about this poem form is #3 rhyme scheme.

There are several different kinds of sonnet rhyme schemes, but the one I find easiest to write is called the Shakespearean after, you guessed it, William Shakespeare. You know he wrote Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet and those other plays, but you maybe didn’t know he was an incredible poet who wrote sonnets.

His rhyme scheme is

ABAB

CDCD

EFEF

GG

What is that gibberish?

That is the rhyming pattern of the end words of each line. And notice that I gave you 14 letters because you have how many lines in a sonnet? 14—you’ve got it.

So look at this sonnet. If I dissect the rhymes, you see the first ending rhyme is

By, which gets the letter A. Since the next word doesn’t rhyme with by, it gets the next letter in the alphabet, B.

But then I rhymes with By, so it gets the letter A as well. And Roam rhymes with home, so it gets a B.

If you follow that pattern, see the rhyme scheme below:

Come here, Little Red, always covered by A

warm velvet, take this cake to your Gram’s home B

now—you two sweets will lift her spirit. I A

warn you, dear one: stay the path. Do. Not. Roam. B

Come here, Little Red—tell me where you’re go- C

ing. To see your Gram? Hmmm. You should pick her D

flowers! Far from the path, many kinds grow. C

(While you’re gone, I’ll make a tasty transfer.) D

Come here, Little Red—what big hands I have, E

ay? Well, let me show you how they’ll hug you— F

Big teeth? They make eating easy. I’ve had E

one snack so far, and you’ll be number two. F

Come here, Little Red—climb out; the beast’s dead. G

Be careful whom you trust and where you’re led. G

That’s the Shakespearen Sonnet rhyme scheme.

In the end, if you can remember those three things,

1) 14 lines

2) 10 syllables per line

3) rhyme scheme like Shakespeare’s

ABAB CDCD EFEF GG

you can tackle writing a sonnet, which I think you should try.

But even if you don’t, I hope you can better appreciate sonnets. If you want to see how I put 12 fairy tales into this form, you can get my book by clicking on the covers at the start of this blog. I want to thank you for learning about poetry. Happy reading, and happy writing!