In Defense of the Sonnet

By Professor Jessa R. Sexton

When I was in elementary school, I can remember arguing with my teacher that a poem didn’t have to rhyme. My first attraction to poetry as an art form was the freedom I felt in writing it. My mom would quickly say that made incredible sense, given my calmly-rebellious nature. I like rules—when I make them.

As I grew older, I began to experiment, but in the backwards way from how many artists do. I decided to test my limits, first because a teacher told me to, and second because I was curious: how creative could I still be within the confines of a set poem structure?

The thrill of seeking an answer to this question still inspires me today. And in 2015, I fell madly in love with the sonnet. Though I wouldn’t claim them to be the most difficult poem form to craft, they’ve become my favorite form of poem-unication.

Not everyone feels the same love, and I can understand. However, I’d like to share a little about why you should give sonnets a try, both in reading and—if you are so inclined—in writing. In any case, by looking at the basics, the blending, and the beauty of this form, I hope you can develop a higher admiration.

Basics

What is a sonnet?

All sonnets have fourteen lines, each line with ten syllables.

This ten syllable line is said to have iambic pentameter. (An iam means two syllables; pent means five; two times five equals ten, so the meter is ten syllables!)

The three most popular sonnet form rhyme schemes are listed below:

Italian

a b b a a b b a

The remaining 6 lines is called the sestet and can have either two or three rhyming sounds, arranged in a variety of ways:

c d c d c d

c d d c d c

c d e c d e

c d e c e d

c d c e d c

c d c d e e

Spenserian

a b a b b c b c c d c d e e

Shakespearean

a b a b c d c d e f e f g g

Oh—and I made up my own, because I dream of one day being a famous sonneteer as well.

Hilliardian

abcd abcd efgefg

Blending

Now that you’ve seen the basic mechanics behind the sonnet, you might be thinking something such as this: But…why? Why would you write within those set parameters and restrictions?

I’m so glad you asked. So many reasons abound. I’ll share a few.

- The challenge! As I mentioned before, being creative within confines is an excellent exercise. Just as your body grows stronger and more tone with physical exercise, your craft will develop when you mentally challenge your abilities by playing with poetic mechanics such as the way words sound, lie on the page, or flow—or by working through various poem forms.

- The connection! Form and function are both important terms in art. In poetry, the blending of these brings a deeper meaning. A sonnet seems strict and rigid. When you pair this form with the function of discussing something holy, deep, or lovely, you create a marriage of form and function. When you pair this form with the function of discussing something funny, broken, or mundane, you create a juxtaposition in form and function. Either way, you are using the form of the sonnet to communicate on a deeper level.

- The conception! When I have an idea, for some reason I find an incredible journey of discovery when mulling it over through sonnet-writing. Other artists have their favorite modes of brainstorming, of breaking down thoughts and putting them back together. For me (and maybe for you, if you’ll try), sonneting helps me begin and end an idea I want to examine.

Beauty

I have two poems solidly memorized. The first is by William Carlos Williams.

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

I think you can see why that one has easily stayed with me. But the second poem is Shakespeare’s sonnet that begins “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” The stark contrast between these two poems is obvious. For the longest time, I feel we’ve jumped up to defend the beauty of the simple, the every day. And while this has merit, we also need to remember the beauty of the complex.

A spider can weave all day, and a single thoughtless swipe of my child’s hand can destroy her work. That delicate complexity must be rebuilt. And when I write a sonnet, I try to craft something solid enough to withstand the apathy it might attain. Of course disinterest can destroy, but half the time I write for myself. Though I love to share a poetic success, the reason I step up to the sonnet in the first place is to find what beauty I can discover when I give myself the chance to walk through the iams and the rhyming and the fixed fourteen lines. Because if I make it through all of that, and my final product flows off my tongue like a song, then I’ve proved to that calmly-rebellious elementary school poet that there’s a different kind of freedom in form.

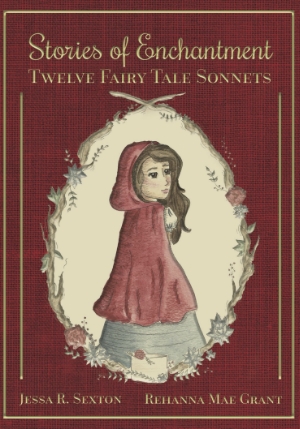

COMING SOON are two new books by author Jessa R. Sexton and illustrator Rehanna Mae Grant: one for all ages (pictured above) and one aimed more towards kids called Little Stories of Enchantment: Twelve Fairy Tale Sonnets for Children. Click on the cover to learn more.